Do your interviewers get it right? Quantify real interview success

This article originally appeared in Graduate Recruiter Magazine, published by the Association of Graduate Recruiters .

In recent years, there has been a significant increase in the number of tools used to help assess candidates, including personality tests, cognitive tests, and gamification. Notwithstanding the insights these tools may yield, interviews are still at the core of recruitment, and especially of the final decision. However, little has been done to assess how effective people are at conducting interviews, and whether they are able to correctly make the critical hiring decisions.

We all know the pains of having the wrong person on our team, but it’s equally damaging to send top talent to your competitors when good candidates are incorrectly turned down.

No interviewer goes into their interviews planning to make poor decisions; however, there is an abundance of evidence showing that many mistakes are being made. If we can measure the effectiveness of interviewers and understand what is driving their decisions, we can take action to improve their success rates.

Let us first explore how interviewer effectiveness can be measured, then what we can learn from the results, and finally we will discuss how you can perform this analysis for your organisation.

Defining interviewer effectiveness

It is hard to define what effective interviewing is.

Let us take Charlie, a manager at a professional services firm, who is conducting interviews for his company’s graduate recruitment. Charlie has multiple objectives when he is interviewing, such as:

-

Correctly identify candidates who will become high performers in the company

-

Remain unbiased in his assessments

-

Clearly explain the role to the candidate

-

Provide the candidate with the best experience to build the company’s brand, and

-

Effectively represent the firm and uphold the firm’s values

Firstly, we must define what ‘become high performers’ means. We have found that different industries, companies, and even roles within the same company, define this differently.

Charlie’s company defines graduate recruitment success as “ candidates hired, who are meeting or exceeding performance expectations two years after being hired ”. I should mention that reaching an agreement on this definition does require some healthy debate. Some say success is achieved when new hires pass their probation period. Others argue for performance at six months, while some have made a case for a much longer time period. Whatever the definition, we can run similar analyses.

With this definition, we can create the following success table. Charlie has made the right decision when:

| Charlie says... | His colleagues... | The candidate is... |

|---|---|---|

| Hire | Agree | Hired and is performing well 2 years after |

| Don’t hire | Disagree | Hired and is underperforming (or leaves) within 2 years |

| Hire | Disagree | Not hired, and joins a close competitor and is there 2 years later |

| Don’t hire | Agree | Not hired, and joins a non-competitor or joins a competitor, but leaves within 2 years |

Following the same logic, we can also construct a table that shows when Charlie has made the wrong hiring decision. With these tables, we can create an “Interviewer Success Index” for Charlie that tracks how often he is making the right decisions.

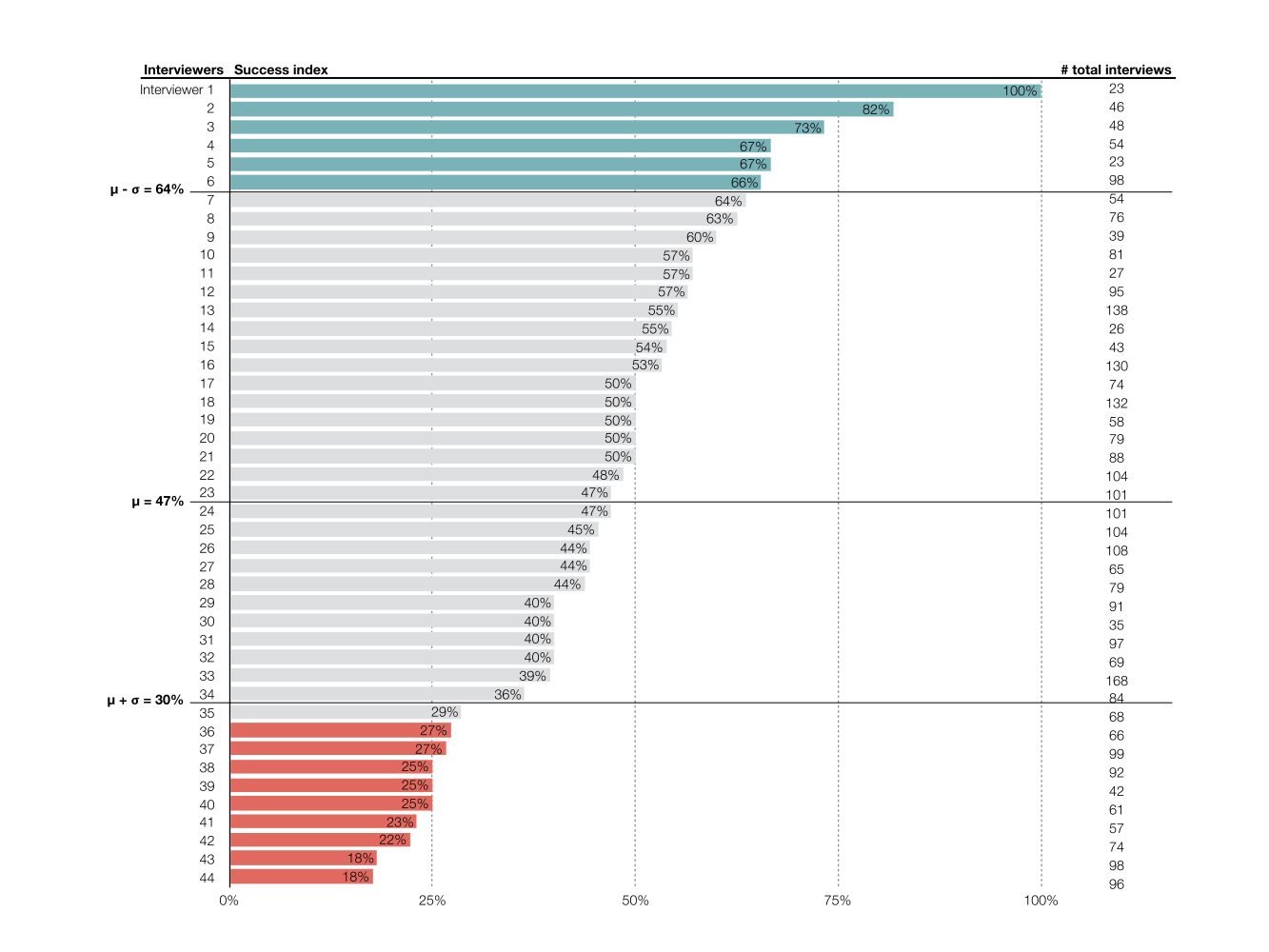

The following chart shows the ranking of different interviewers in a professional services firm. Interviewer 1 has always made the correct hiring decision across all of his/her 23 interviews.

There are a few striking observations from this figure:

-

There is a wide distribution of interviewer success

-

The average success rate is 47%, just below the 50% success you would expect from flipping a coin to decide whether to hire or not

-

There are some interviewers who are consistently making the right decisions, and some who are fairly consistently making the wrong decisions.

Interesting…but ‘so what’?

Perhaps the most striking observation is that there are interviewers who are consistent - both consistently right and consistently wrong. The question that needs answering is “What do the best performing interviewers know that the rest of us do not?”

In this particular example, the answer is — not much. Through some distribution and bias analysis, (the details of which I will spare you), we were able to identify three types of interviewing styles:

-

Type 1: interviewers who follow the processes the company has defined, meticulously filling in their evaluation forms, and making their hiring decisions based on their evaluation;

-

Type 2: interviewers who don’t follow the process, but do ensure their feedback forms conform with the decision they’ve made through other means (i.e. retro-fitting evaluation forms);

-

Type 3: interviewers who contradict their evaluation forms with their hiring decisions (e.g., scoring candidates highly, but turning them down, or scoring candidate poorly, but hiring them anyway). These interviewers seem to be assigning scores and hiring decisions randomly.

This example is not unique. We consistently see these patterns across industries and companies.

So how effective is each type of interview style?

Type 2, those who retro-fit their evaluation forms, are the bottom performers. Not surprisingly, those who contradict themselves (Type 3) have a success rate broadly in line with flipping a coin, and interviewers that follow the company’s process (Type 1) are its top performing interviewers . This last point, coupled with some further analysis, can show how effective the recruitment process is.

We do, on occasion, find a few clairvoyants - interviewers who do not follow the company’s processes, but achieve extraordinary results. As any scientist would do, we track them down, buy them a coffee, and study their techniques very closely.

So what is the outcome of this analysis? Charlie’s company implemented a few changes:

-

Since his company conducts interviews in pairs, they strategically paired their interviewers

-

They prioritised the interviewers, ensuring the top performing interviewers are more active

-

They provided feedback to the interviewers (along with their bias tendencies) and introduced stricter interviewing guidelines and training.

How can you replicate this analysis for your organisation?

To replicate this analysis for your organisation, you will need:

-

An agreed definition for what recruitment success is for your organisation. From our experience, this usually requires a short workshop with the key stakeholders.

-

Historic interview data (the more the better), including:

-

The interviewer

-

The candidate

-

Interview feedback (competency scores, or otherwise)

-

The hiring decision (hire / turn down)

-

Tenure and performance results of those candidates hired

-

-

Some patience to look up candidates turned away and remotely assess whether they’ve been doing well in their career or not.

With this data, you can then construct both the ‘hiring successes’ and ‘hiring failure’ tables as described above. The Success Index can then be calculated by dividing the number of successes by the total number of interviews conducted.

If you would like to get started with this analysis in your firm,

get in touch

— it’s what we do best.

Subscribe to the latest data insights & blog updates

Fresh, original content for Law Firms and Legal Recruiters interested in data, diversity & inclusion, legal market insights, recruitment, and legal practice management.